A few years ago, on tour in Paris, I was returning from a visit to the Shakespeare & Co. bookshop. A passing young man approached me asking “Pouvez-vous m’aider?”. He had finished his studies he explained and was returning home to Congo the following week. Could I help by buying one of his textbooks? It was “Le Déclin des Idoles”. I would have little use for it. He was pleasant however, so I offered him slightly more than face value. He casually asked where I came from, but when I answered “D’origine, je suis Polonais” he immediately tried to return the money, saying “There was that General…”, “Kościuszko?”, I suggested. “Exactly!” he replied, “please at least come and meet my friends”.

“That General”, Tadeusz Kościuszko (kosh-tshoo-shko), was indeed a unique European figure. Once described by his friend, Thomas Jefferson, as the purest son of liberty, he believed that “we are all equals, riches and education constitute the only difference”. It was that person who was known about and admired by the mixed group of African students I met that evening in Paris.

Kościuszko, heavily involved in the struggle for Poland’s liberty, was doomed to a life of exile while the surrounding powers partitioned his country. His 1776 arrival in the American colonies led to his involvement in the American revolutionary war with outstanding results. After serving 7 years of military service he was rewarded with land and had accumulated considerable back pay. These he left in his will, entrusted to Thomas Jefferson, before returning to Europe. He specified the funds should be used to buy Jefferson’s slaves’ freedom and more particularly to educate them. Back in Poland, during a chaotic period of revolutionary upheaval, a black man from Haiti, Jean Lapierre, offered him his services as aide-de-camp and became a trusted assistant to the general during the revolt against invading Czarist-Russian armies. In many matters, particularly social, historians consider Kościuszko to be a man well ahead of his time.

Kościuszko died in exile in Switzerland. He was living there in relative poverty, having freed his peasant farmers from their obligations. He was, however, seen as an essential and inspiring figure and a memorial was established near Kraków.

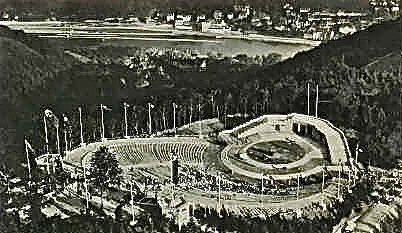

People came from all over Poland bringing large and small amounts of soil to create a mound well over 100 feet in height. When it was completed (1823) urns, with earth from the many American battlefields he had fought in, were buried in it. A circular pathway leads to the top. It is an unmistakable presence on the edge of Kraków.

This landmark is even echoed in distant Australia. Sir Paweł (Paul) Strzelecki, known for his expeditions in North and South America, travelled through the Snowy Mountains in the Australian Alps. There, he saw a peak that reminded him, in shape, of the mound at Kraków. Having climbed to the 7000ft summit in a day, he named it after Kóciuszko, the hero of democracy.

In Poland Kóciuszko is also celebrated in the Racławice Panorama, one of the largest oil paintings in the world (114x15m) commemorating the victory at the 1794 Battle of Racławice, where peasant soldiers, armed with scythes, attacked the Czarist-Russian troops. The canvas, rolled up, was hidden from the Nazi searches and only emerged years after WWII. It now attracts 400,000 visitors annually to Wrocław. For those with extra reading time, it is worth exploring the outlines of Polish history by historian Norman Davies in his appropriately titled “God’s Playground”. Or, more intimately, in James Michener’s 1983 bestseller “Poland. A Novel”.

After the war, and 20 years spent in Spandau prison, Speer moved back to Heidelberg and lived in a villa above Heidelberg Castle. His son was also an architect but the two were estranged until his death in 1981 in London. He was on his way to a BBC interview on his bestselling autobiography. To his death, Speer always denied knowledge of the Holocaust and is said to have donated a good part of his publishing income to charitable Jewish institutions.

After the war, and 20 years spent in Spandau prison, Speer moved back to Heidelberg and lived in a villa above Heidelberg Castle. His son was also an architect but the two were estranged until his death in 1981 in London. He was on his way to a BBC interview on his bestselling autobiography. To his death, Speer always denied knowledge of the Holocaust and is said to have donated a good part of his publishing income to charitable Jewish institutions.

p, land of the endangered Amur Tiger. There are less than 30 left in China and 400 in Siberia, some of which prey on bears. There is also an Amur leopard, though only about 45 adults remain in the wild. Earlier in 2014, Vladimir Putin released three tagged Amur tigers into the wild in this region. One, a male called Kuzya, made headlines by quickly choosing to cross the river into China, where local officials welcomed the event, promising that “if necessary, we can release cattle into the region to feed it” .Siberia remains in the news…

p, land of the endangered Amur Tiger. There are less than 30 left in China and 400 in Siberia, some of which prey on bears. There is also an Amur leopard, though only about 45 adults remain in the wild. Earlier in 2014, Vladimir Putin released three tagged Amur tigers into the wild in this region. One, a male called Kuzya, made headlines by quickly choosing to cross the river into China, where local officials welcomed the event, promising that “if necessary, we can release cattle into the region to feed it” .Siberia remains in the news…

Stories of the great treasure, said to be buried with him, have always circulated among Mongol tribes.The site of his former palace is located about 150 miles from today’s capital, Ulaan Bataar. Despite rumours and many searches (even, most recently, by satellite), nothing has ever been found. In the city itself, the main city square is dominated by the seated statue of Chingghis (Genghis) Khan on the approach to the National Museum.

Stories of the great treasure, said to be buried with him, have always circulated among Mongol tribes.The site of his former palace is located about 150 miles from today’s capital, Ulaan Bataar. Despite rumours and many searches (even, most recently, by satellite), nothing has ever been found. In the city itself, the main city square is dominated by the seated statue of Chingghis (Genghis) Khan on the approach to the National Museum. to sheep”). Traditionally a nomadic people, they were accustomed to live in relative isolation from each other. Once guided by Shamanism then by Buddhism, they were ruled from the legendary capital of Karakorum, the center of power moved later by Kublai Khan to Shengdu, an event imagined by poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in his memorable verse

to sheep”). Traditionally a nomadic people, they were accustomed to live in relative isolation from each other. Once guided by Shamanism then by Buddhism, they were ruled from the legendary capital of Karakorum, the center of power moved later by Kublai Khan to Shengdu, an event imagined by poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in his memorable verse the city still has some of the lowest crime rates in Asia.

the city still has some of the lowest crime rates in Asia. here. A popular restaurant, DGH, is subtitled “Dreams Get Happiness” while another sign reads “DESTROY, Hair and Beauty Salon”?! The largest commercial enterprise is the STATE DEPARTMENT STORE, “All Needs are Fulfilled,100% cash back guarantee”. It is full of Western and UK brands that, according to our British fellow-travellers, are offered at 2/3 the price of Marks and Spencer.

here. A popular restaurant, DGH, is subtitled “Dreams Get Happiness” while another sign reads “DESTROY, Hair and Beauty Salon”?! The largest commercial enterprise is the STATE DEPARTMENT STORE, “All Needs are Fulfilled,100% cash back guarantee”. It is full of Western and UK brands that, according to our British fellow-travellers, are offered at 2/3 the price of Marks and Spencer. While two of our intrepid travellers, Bob and Geraldine, head out of the city to see the enormous (40 meters/about 130 ft tall) Genghis Khan statue by the Tuul river, the rest of us leave for the dramatic rocky Terelj National Park. The tour is led by our local guide Buyana, whose name, we find out, means “heavenly light”. It is a chance to catch a glimpse of wild Mongolia.

While two of our intrepid travellers, Bob and Geraldine, head out of the city to see the enormous (40 meters/about 130 ft tall) Genghis Khan statue by the Tuul river, the rest of us leave for the dramatic rocky Terelj National Park. The tour is led by our local guide Buyana, whose name, we find out, means “heavenly light”. It is a chance to catch a glimpse of wild Mongolia.

to Russian tradition and a fascinating visit to an Old Believer community, exiled to Siberia centuries ago for refusing to accept reforms aligning the liturgy with that of the Greek Church. During the visit we have lunch, enjoy village songs and jokes, admire the colorful painted houses and their gardens. Soulful Russian poet Yesenin, once lover and husband of Isadora Duncan, came from an Old Believer peasant family. We hear about even more traditional Old Believer communities such as those in Estonia that still follow ancient prohibitions such as the one where men who die without a beard have to be buried in an unmarked grave or another about women who, unable to enter a church bareheaded, must have their scarves pinned under their chin for tying a knot is symbolic of the suicide of Judas by hanging. Otherwise the traditional icons are similar, the “onion domes” of churches still represent the flame of a candle, while the lower bar on the crucifix, at an angle to the cross, represents pointers signifying up to heaven, down to hell, a reminder of the choices made by the two thieves crucified on either side of Christ on Golgotha. Another window on the Russian soul.

to Russian tradition and a fascinating visit to an Old Believer community, exiled to Siberia centuries ago for refusing to accept reforms aligning the liturgy with that of the Greek Church. During the visit we have lunch, enjoy village songs and jokes, admire the colorful painted houses and their gardens. Soulful Russian poet Yesenin, once lover and husband of Isadora Duncan, came from an Old Believer peasant family. We hear about even more traditional Old Believer communities such as those in Estonia that still follow ancient prohibitions such as the one where men who die without a beard have to be buried in an unmarked grave or another about women who, unable to enter a church bareheaded, must have their scarves pinned under their chin for tying a knot is symbolic of the suicide of Judas by hanging. Otherwise the traditional icons are similar, the “onion domes” of churches still represent the flame of a candle, while the lower bar on the crucifix, at an angle to the cross, represents pointers signifying up to heaven, down to hell, a reminder of the choices made by the two thieves crucified on either side of Christ on Golgotha. Another window on the Russian soul.

s ! Locals point out Baikal is the ideal crime site, as there is absolutely no evidence left.

s ! Locals point out Baikal is the ideal crime site, as there is absolutely no evidence left.

That evening there were cocktails and a special Caviar Dinner. Piano music in the lounge bar brought a discussion on how Moscow composer Boris Tchaikovsky (no relation to Peter Ilyich) was moved to write his symphonic poem on “The Wind of Siberia” (1984), considered a “pictorial masterpiece” by critics. Irkutsk novelist Valentin Rasputin was also mentioned as a controversial environmentalist (maybe stimulated by his own home village, Atalanka, being flooded as part of a major dam project ). He is seen as trying to protect and preserve northeastern Siberia from what Moscow authorities consider as ripe for exploitation or development. We note the stop at Polovina to come. It means “half-way” and is located as a marker station 4644 kms. from Moscow. There are towns with warning names such as Zima (meaning “winter”) before reaching much visited Irkutsk and Baikal, the world’s deepest freshwater lake.

That evening there were cocktails and a special Caviar Dinner. Piano music in the lounge bar brought a discussion on how Moscow composer Boris Tchaikovsky (no relation to Peter Ilyich) was moved to write his symphonic poem on “The Wind of Siberia” (1984), considered a “pictorial masterpiece” by critics. Irkutsk novelist Valentin Rasputin was also mentioned as a controversial environmentalist (maybe stimulated by his own home village, Atalanka, being flooded as part of a major dam project ). He is seen as trying to protect and preserve northeastern Siberia from what Moscow authorities consider as ripe for exploitation or development. We note the stop at Polovina to come. It means “half-way” and is located as a marker station 4644 kms. from Moscow. There are towns with warning names such as Zima (meaning “winter”) before reaching much visited Irkutsk and Baikal, the world’s deepest freshwater lake. , inconvenient critics such as Romantic writers Lermontov (“A Hero of our Time”) and Pushkin had been sent to the Caucasus to cool off, but this was a more serious matter. The Decembrists, as they became known, came from the Russian elite. Their main leaders were hanged, but large numbers of exiles from aristocratic families were dispersed over Eastern Siberia. They gradually made Irkutsk their principal centre, at the same time transforming cultural awareness in the whole region. A particularly poignant aspect of their exile was the heroic determination of their wives and fiancées who abandoned great wealth, comfort and even their children, to support their rebellious, liberal spouses and create an island of culture in the wilderness ,an aspect which still influences the city today. It is this which is brought out in our Golden Eagle excursions when we see the paintings, portraits and landscapes at the Irkutsk Art Gallery, before visiting some of the carefully preserved wooden houses, long gone in most other cities.

, inconvenient critics such as Romantic writers Lermontov (“A Hero of our Time”) and Pushkin had been sent to the Caucasus to cool off, but this was a more serious matter. The Decembrists, as they became known, came from the Russian elite. Their main leaders were hanged, but large numbers of exiles from aristocratic families were dispersed over Eastern Siberia. They gradually made Irkutsk their principal centre, at the same time transforming cultural awareness in the whole region. A particularly poignant aspect of their exile was the heroic determination of their wives and fiancées who abandoned great wealth, comfort and even their children, to support their rebellious, liberal spouses and create an island of culture in the wilderness ,an aspect which still influences the city today. It is this which is brought out in our Golden Eagle excursions when we see the paintings, portraits and landscapes at the Irkutsk Art Gallery, before visiting some of the carefully preserved wooden houses, long gone in most other cities.

triumphant rendering of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto (it is absolutely worth seeing, at least

triumphant rendering of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto (it is absolutely worth seeing, at least